Shooting in the dark

The small car park at the start of the Ridgeway is half full of camper vans. No one is stirring at 6:45am and there are no other walkers when I bounce the car over the uneven surface of the car park, grab my camera and start up the ancient track. The evening before I checked both dawn and sunrise times hoping to arrive 30 minutes before the first to spend the early part of my walk in the dark. Although I have recently embraced spending more time the dark, I kiss the dark only twice each day, first thing in the morning and last thing at night, in the garden, encouraging the dog to piss. But I got my alarm timing wrong today and by the time I arrive at the car park there is already enough light to see across the downs to Silbury Hill, the valleys beyond Avebury to the west, and the church towers of West Overton and Fyfield in the South.

On the path I am greeted immediately with a spirit gift from the nighttime world, a barn owl ejecting itself with some urgency off a fence post as I (unknowingly) approach in a cough of cold morning air. I grab my phone to film but only manage to shoot two seconds of the inside of my pocket. Classic dad move. The owl appears for a second showing a minute later and I point my proper camera at it and shoot five or six photos of its distant silhouette flying low over a line of trees. I have been this close to a barn owl three times in my life: in primary school when birds of prey were brought in and we could choose between eagle and owl to be photographed with – I chose owl – and half a dozen years ago in my local park. That morning I managed to operate my phone less like my dad and shot a minute or two of a ghostly barn owl hunting in the field with the two dead oaks at a similar dawn-ish time.

The owl shakes me off and I point my camera at other, more static downland features. Namely stands of beech and the distant forms of hills. I check my camera display to see what kind of detail I’m capturing and it looks back, blankly. Shooting in the dark. Hopefully the edit at home will coax some joy from the dark rectangle staring back at me from the LCD.

It’s colder than the forecast claims. The wind whips around my cap and I consider pulling on my hood before remembering it muffles the outside world whilst shrouding it in its own synthetic sound. This is less preferable to nature sounds, even if my ears take a beating from the wind. My steps are measured by the evacuation of birds from the hedge to my right that shriek comically and call foul as I come close. Higher up, communions of redwing make their own Saturday morning pilgrimages. The hooting and hollering continues to my right. I am a magnet turned the wrong way, repelling birds as I traipse up the path. A police car blue-lights its way east along the A4 like an automaton across a diorama. Pink dawn soaks through cloud gaps here and there and I photograph a star through one such crack in the firmament before the latest and largest hedgerow evacuee, a buzzard, steals my attention trying to regain his composure with a couple of powerful flaps into the crisp, frisky skyland.

Suddenly it’s day. The dark/light balance has tipped without me clocking it and, lo! I can see everything. Colour instantly comes to things, and the abstract world of night is quietly ordered into daytime. Two stonechats are fighting in a ball down to my left. With all the authority of a supply teacher, my presence only briefly halts their misconduct and they quickly return to the quarrel, brawling their way noisily up the path. A radio plays faintly from a tent pitched in the corner of a field of brassicas. I hadn’t seen it and the sudden company at this time of morning feels eery.

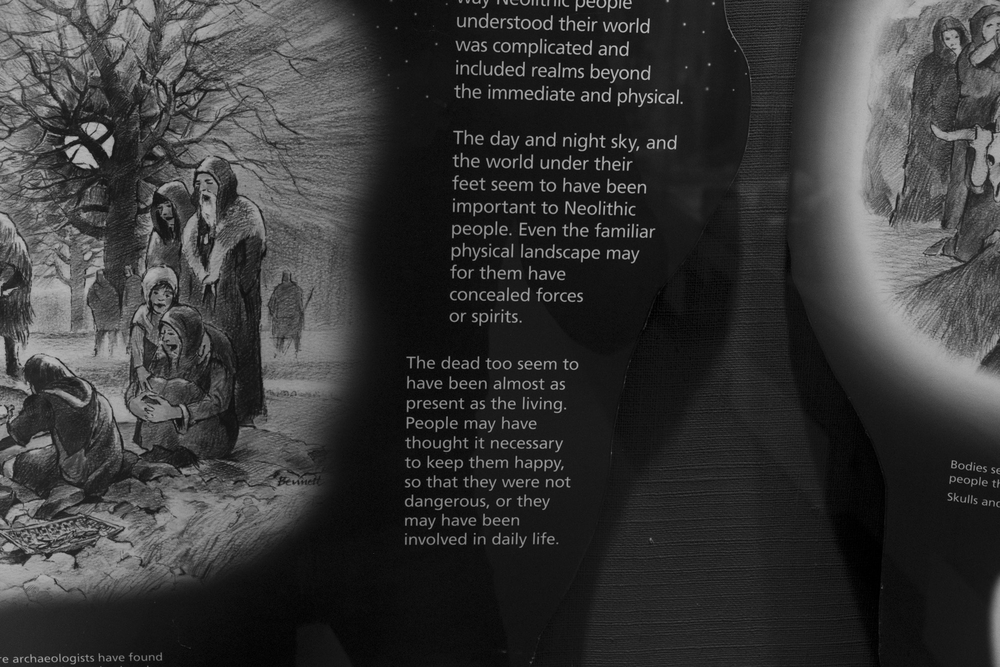

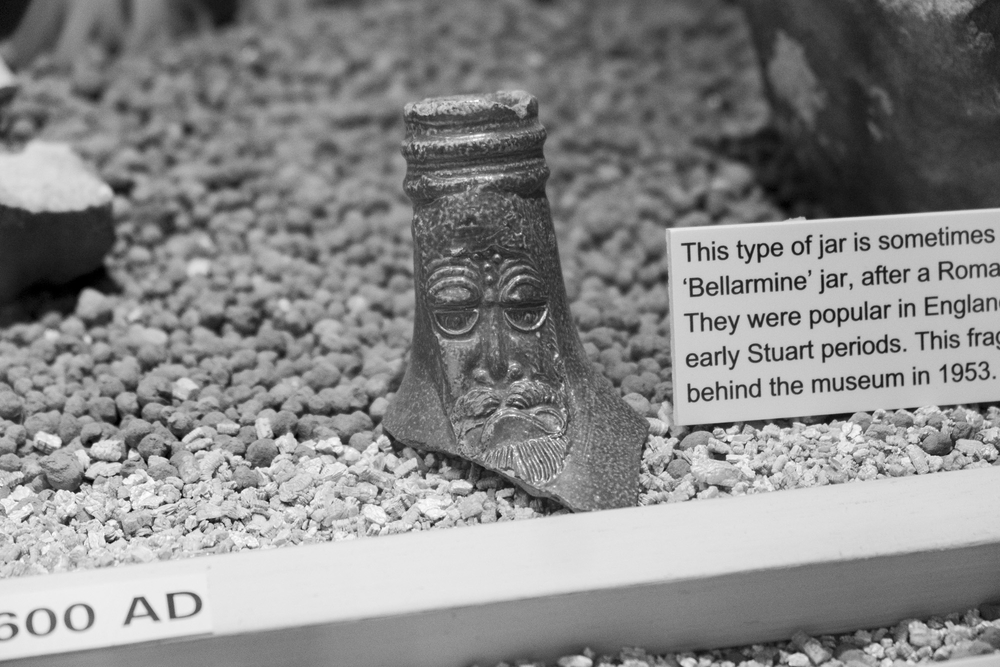

I have come to look for The Polisher, a sarsen stone in a field of sarsen stones that bears marks of neolithic tool-sharpening. It’s one of dozens of notable stones up here, vestiges of our curious, unknowable past. Later in the day the museum in Avebury confirms that we have no real idea what the purpose of these configurations was: “No one knows who they were, or.... what they were doing” goes the enduring wisdom of Nigel Tufnel. But they left their stony leftovers nonetheless, and here I am sniffing over the crumbs.

Yarrow, ragwort and knapweed are the last flowering plants of the year up here on the Ridgeway. Vestiges too, of summer, confused by the mild November weather. Hedges of spindleberry and hazel, more birds in clamouring alarm. I exchange "hi's" with a woman pushing a bike in the opposite direction, phone wedged at her ear, two sighthounds pulling out in front.

Kestrel. Wren. Fieldfare. Finally The Polisher Stone. I walk around it. Make a video. Take some photos. Run my hand down the dead straight, glass-smooth marks. Close my eyes. Try to commune with the dead but instinctively mutter a prayer instead. Perhaps they are the same thing. I open my eyes and everything is slightly different, but not really. It’s too abstract a thought that 4000 years ago people regularly pulled off the path here to sharpen their tools on this one stone. I mean, what the actual?

Heading back toward the car I choose between two triangular walks and decide to take the second and head further into Fyfield Down to visit the Valley of Stones and Devil’s Den. Ten minutes in I meet a man and his black dog looking between the stones for waxcaps. He’s found and photographed twelve varieties. He has tattoos everywhere his winter gear reveals skin, a scorpion tail poised to strike from the left side of his neck. My enthusiasm for mushrooms exhausts itself against his boundless knowledge and he relents, pointing me in the direction of Devil's Den.

Suddenly, without warning I meet my own black dog and the day tumbles to gloom. The valley sides, the river of rocks are heavy-hearted. I am heavy hearted. The joy that brought me out, saw me to the Polisher Stone, that underpins my curiosity is suddenly, inconsolably snuffed out. I decide to ignore this new feeling and push on past the Toad Stone (which looks as it sounds). The Devil’s Den is still twenty minutes down this lonesome valley, with no direct path back to the car. I’d have to retrace my steps, a habit I have hated ever since I was a child as it meant knowing exactly how far I still had to go. I decide to quit, a habit I find equally irksome, and turn to follow a livestock trail up the valley side back to the ridge summit. My mood temporarily lifts before I turn into another valley with an ancient, but misshapen farmhouse next to an enormous corrugated steel clad barn that sends me into another grey cloud of depression. I am past the farm and into the trees before my mood ticks up closer to baseline again. It’s a tree full of starlings that does it. I watch as they repeatedly vacate in giant plumes and resettle again. And then the familiarity of the path beneath my feet fills the day with daylight again.

I spend a lot of time alone in the countryside and it’s only in such moments of despair that I actually feel lonely. Resonant landscape gives me everything, but the opposite is somehow devastating. Sometimes it’s just the disappointing bend in the path, or a scrappy band of trees. Quite often it's a human intervention that makes me feel blue.

A good journey into the landscape involves some suspension of reality. It’s definitely often an escape, but also a reconnection to quieter parts of myself and an opportunity to process thoughts and feelings and to recalibrate. I project all sorts of things onto landscapes, and in turn they sometimes kick back. Whilst the landscape is always ambivalent, I am not – and I project that. When I perceive that it's not being "properly" reflected back, it registers as a lack, and thus effects me negatively, leaving no story in the field worth telling. That's today's analysis, anyway. Hmmm.

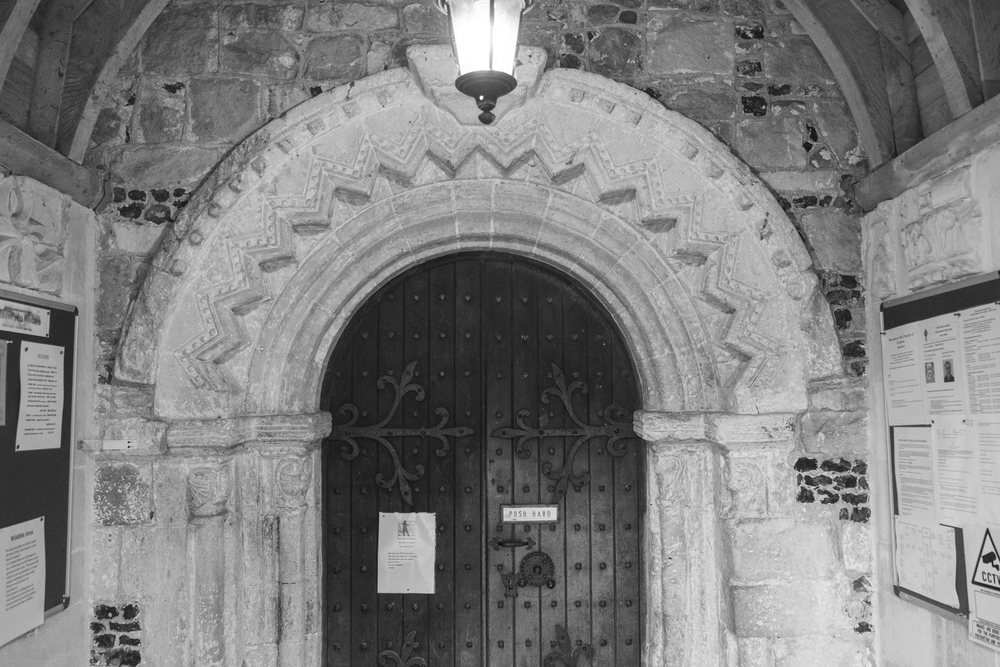

Everything folds neatly back into connexion when I park at Avebury and walk past the trim, picture book cottages, through the lychgate and into St James’s church which turns out to be both beautiful and full of historical features, adroitly noted in the paddle-mounted, typewriter-written potted histories I carry with me as I travel back to the ninth century. I shell out for a cream tea (coffee, in fact) at the National Trust cafe. A group of retirees in technical walking gear are dotted across the tables, brandishing walking poles and discussing the new series of Wolf Hall. I stare out the window, at the pond, the slow stream of faces coming in from the cold. I eat my cream tea the Devon way and gulp down my americano. I visit the museum and the manor garden before finally, inevitably, the stones call to me and I do a lazy loop around the raggle taggle community of Avebury rocks. It’s elevenses by the time I return to the car and the day is in full swing. Though the November sun never ventures high into the sky, it’s bright enough to remind me that I have, at least temporarily, left the dark behind.

Photos

Derek Jarman’s 1971 film A Journey to Avebury is a trippy ten minute document of an approach into this most massive of stone circles. It’s shot in Super 8. When I loaded up photos from this trip onto my computer and dragged the exposure slider to it’s absolute limit, the detail I was hoping for when I shot the photos was indeed there, but with unexpectedly similar qualities to Jarman’s film. I like these early morning shots and have kept their colour. Elsewhere I’ve switched to black and white, another suspension of reality that I’m happy to hang with.